One of the benefits of having worked in so many mediums – print, television, stage, online, stand-alone interactive and film – is that I’ve learned a variety of storytelling techniques that are transferable among platforms.

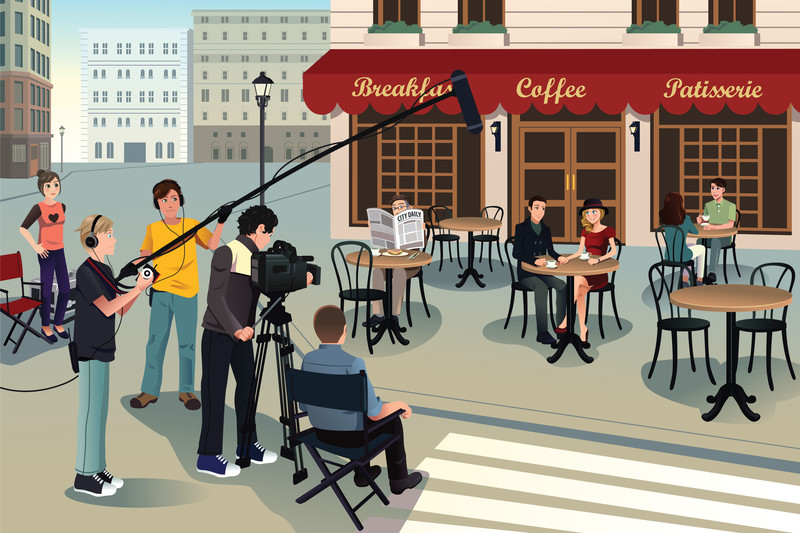

There’s something in the combination of having been a stage manager, a TV writer/producer and a film critic that combines to make me a highly cinematic writer. I don’t mean screenwriter, or that I write epic, sweeping stories easily adapted to the screen (I don’t); I mean that I’ve learned the art of visual storytelling, and when I write, it’s as though there were a camera in my head. I tell the story as I see it in the screen of my mind. Here are a few of the things I do…

Click to continue reading on the Resonant Storytelling Substack

Sarah this in a different and fresh look on the writing process. I was wondering f we could feature it tomorrow, our Friday features on our site : http://thewoventalepress.net

All our editors share all our features across most social platforms so it could be added exposure for you. Take a look at the site and see what you think. you can email me referencing this post’s url at editor@thewoventalepress.net

Thanks,

Sandra Tyler

Editor-in-Chief

Thanks so much, Sandra. I’d be honoured. I’ll email you.

One of my beta-readers suggested a similar technique, although not quite so comprehensive as this, Sarah. It’s helpful to get out of the rut of always thinking like, in my case, a writer, to put myself in the mindset of another sort of storyteller. Thank you for adding to the toolbox.

This relates very closely to my work in writing art techniques. I’d live to see more.